Yesterday was my wife, Katie’s, birthday and it reminded me about the so called ‘Birthday Problem’. Or, in a group what is the likelihood of two people sharing a birthday? The result is really quite surprising!

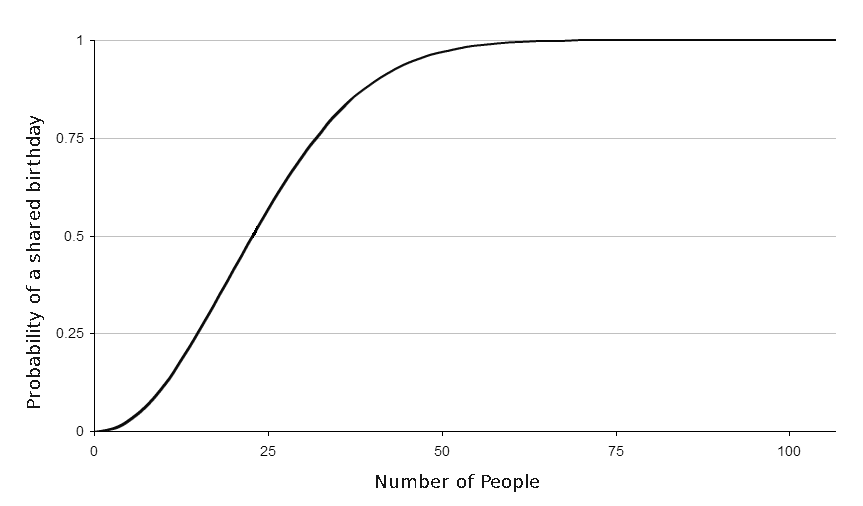

Obviously if the group is of size 366 you are guranteed that at least 2 people must share a birthday (for this, and for the rest of the blog I will ignore February 29th Birthdays, sorry if you happen to be born on that day!) but what is very suprising is that you need only 57 people to have 99% chance and 23 for over a 50% chance. The graph for this is below:

Now, we define \(P(n)\) to be the probability of at least two people in a group of \(n\) sharing a birthday, and \(P^{‘}(n)\) the probability of there not being two people sharing a birthday. Also, since \(P(n)\) and \(P^{‘}(n)\) are the only two possibilities and are mutually exclusive we have that: \[P(n)=1-P^{‘}(n).\] The easiest way of working this out is to first calculate the probability that all \(n\) birthdays are different. For only 1 person the probability that that 1 person does not share a birthday with someone is \(\frac{365}{365}\).

For 2 people, the probability that the second person has a different birthday from person 1 is \(\frac{364}{365}\). The probability that person 3 has a different birthday from 1 and 2 is \(\frac{363}{365}\), and so on and so on. Finally we take note that when events are independent of each other (as they are in this case), the probability of them all occurring is equal to the product of the probabilities.

So we can now calculate the probability of there not being two people sharing a birthday (obviously if \(n > 365\) then \(P^{‘}(n)=0\), this is by the pigeonhole principle). So for \(n \le 365\):

\[\begin{eqnarray*}

P^{‘}(n) &=& \frac{365}{365} \times \frac{364}{365} \times \frac{363}{365} \times \frac{362}{365} \times \cdots \times \frac{366-n}{365}, \\

&=& \frac{365 \times 364 \times 363 \times 362 \times \cdots \times (366-n)}{365^n}, \\

&=& \frac{365!}{365^n(365-n)!}.

\end{eqnarray*}\]

So, the probability of at least two people sharing a birthday in a group of size \(n\) is:

\[P(n)=1-\frac{365!}{365^n(365-n)!}.\]

And this equation gives you the probablility of two people sharing a birthday in a group of size \(n\). If you want to work the probability out for a different value of \(n\) just plug the value you want into the equation above and run the calculations. It is a suprising result and counter-intuitive.