Brewing the Perfect Coffee at Altitude

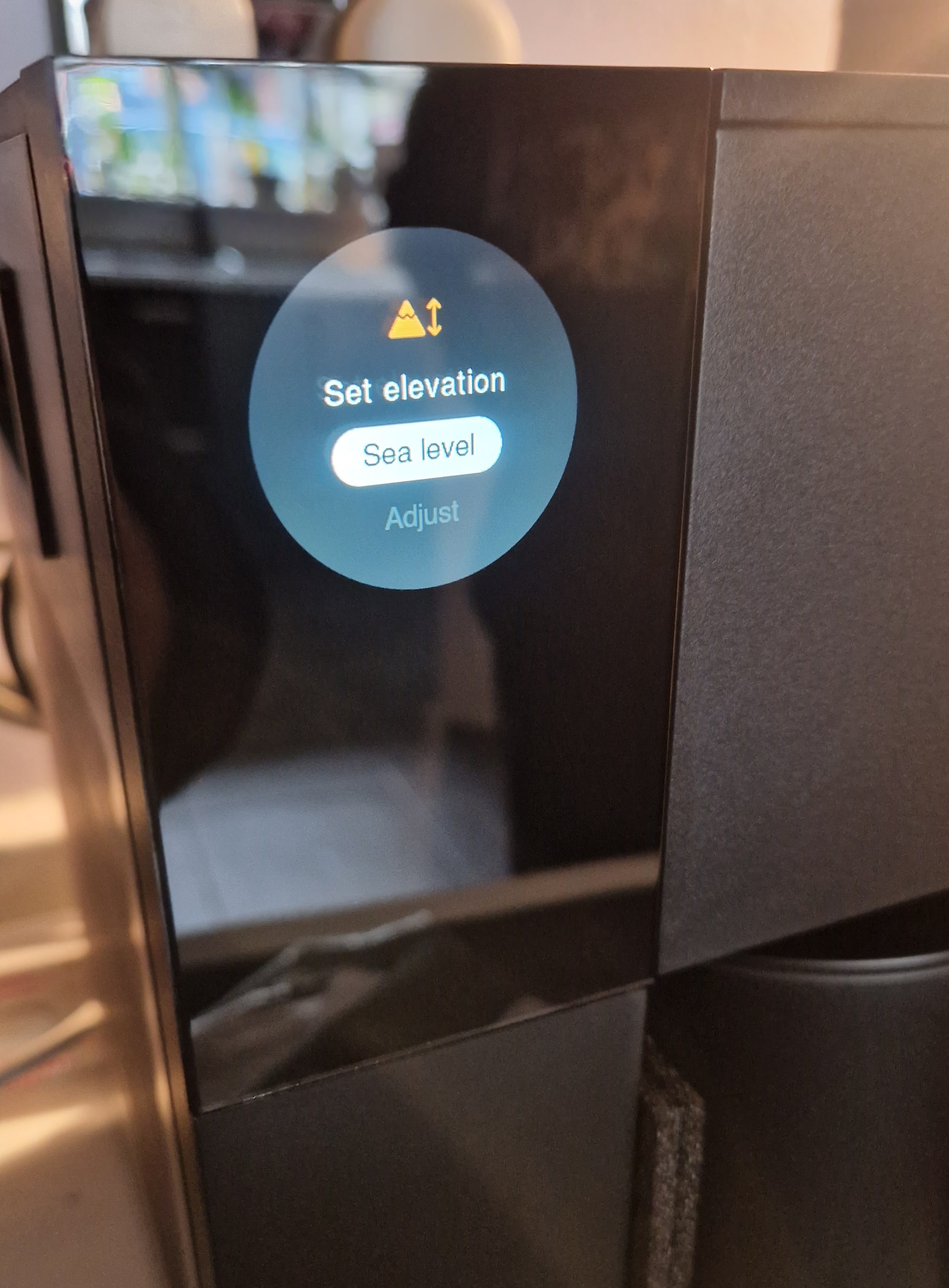

For those of us who consider coffee an essential part of our daily routine, the pursuit of the perfect cup is a never-ending quest. But did you know that your altitude can significantly impact your brew? This post is inspired by my new Fellows Aiden Precision Coffee Maker which, on one of the first set up screens asks:

Perhaps that seems like an odd question, buf if you’ve ever tried recreating your favourite Birmingham coffee experience in Boulder, Colorado (which I have, many times!), you might have noticed something’s a bit “off”. Let’s dive into the science behind why:

It all boils down to atmospheric pressure. The air around us exerts pressure, and this pressure decreases as we go higher in altitude. Why? Essentially, there’s less atmosphere above you pushing down.

Water boiling occurs when the vapor pressure of the water (or really any liquid) equals the surrounding atmospheric pressure. So these changes in atmospheric pressure directly affects the boiling point of water. Lower atmospheric pressure at higher altitudes means water boils at a lower temperature.

The relationship between pressure (P) and boiling point (T) can be approximated using the Clausius-Clapeyron equation:

\[\ln\left(\frac{P}{P_0}\right) = -\frac{\Delta H}{R}\left(\frac{1}{T} - \frac{1}{T_0}\right)\]Where:

- \(P\): The vapor pressure of the liquid at the temperature of interest (in Pascals, Pa). This is what we want to find to determine the boiling point.

- \(P_0\): The vapor pressure at a known reference temperature (also in Pascals). For water, we often use standard atmospheric pressure (101325 Pa) and its corresponding boiling point of 100°C (373.15 Kelvin).

- \(\Delta H\): The enthalpy of vaporization (in Joules per mole, J/mol). This represents the energy needed to change one mole of liquid into vapor at a constant temperature. For water, \(\Delta H\) is approximately 40,700 J/mol.

- \(R\): The ideal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K). This constant relates energy to temperature for gases.

- \(T\): The temperature in Kelvin (K) at which we want to find the vapor pressure (and ultimately, the boiling point).

- \(T_0\): The reference temperature in Kelvin (K). Again, for water, this is often 373.15 K.

Birmingham vs. Boulder: A Tale of Two Cities

Birmingham, UK, sits at a relatively low altitude (around 140 meters above sea level). Water here boils pretty close to 100°C. Boulder, Colorado, on the other hand, is nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains at an elevation of roughly 1655 meters. This significant difference in altitude has a significant impact on the temperature water boils at.

To use the Clausius-Clapeyron equation we first need to calculate atmospheric pressure in Boulder - there are various ways of doing this (getting progressively more difficult) but here it is sufficient to assume a ‘standard atmosphere’ where temperature decreasesd with altitude, and assume that our coffee machine is being used indoors where the temperature is about 20°C, then we can use:

\[P = P_0\cdot\exp\left(\frac{-gM(h - h_0)}{RT}\right)\]Where:

- \(P\): The air pressure (Pa) at altitude \(h\) (this is the thing we want)

- \(P_0\): Air pressure at reference altitude \(h_0\) (as in the previous equation we will use sea level pressure of 101325 Pa)

- \(g\): Acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s²)

- \(M\): Molar mass of air (0.0289644 kg/mol)

- \(h\): Altitude (m) (Boulder is at 1,655m)

- \(h_0\): Reference altitude (m) (here we assume sea level, 0 m)

- \(R\): The universal gas constant (8.31432 J/(mol·K))

- \(T\): Temperature at altitude \(h\) (K) (must be in Kelvin, and so we use 293.15 K)

Plugging those numbers in gives us:

\[\begin{eqnarray*} P &=& 101325\times\exp\left(\frac{-9.81\times 0.0289644\times (1655 - 0)}{8.31432\times 293.15}\right)\\ &=& 83546 \end{eqnarray*}\]So the atmospheric pressure of Boulder is about 83500 Pa (you can also use this online calculator to be more accurate if you want to be, and this also provides more details on air pressure caclulations). Sub this value in (as \(P\)) into the Clausius-Clapeyroin equation and using our other reference values: \(P_0\) (101325 Pa), \(\Delta H\) (40700 J/mol), \(R\) (8.314 J/mol·K), and \(T_0\) (373.15 K) to get:

\[\ln\left(\frac{83500}{101325}\right) = -\left(\frac{40700}{8.314}\right)\times\left(\frac{1}{T} - \frac{1}{373.15}\right)\]Solving the above equation for \(T\) requires a little bit of algebraic manipulation but you should end up with \(T \approx 367.7 K\). Which (by removing 273.15) gives a value of 94.55°C for the boiling point of water for Boulder.

Water boils at approximately 94.5°C in Boulder.

Why It Matters for Coffee

Coffee brewing is a delicate dance of temperature and extraction. Water acts as a solvent, pulling flavorful compounds from the coffee grounds. The ideal brewing temperature for most coffee lies between 90-96°C. But brewing in Boulder presents a unique challenge. With water boiling at a lower temperature, you have a smaller window to extract those desirable flavors before under-extraction occurs. This can result in a sour or weak cup of coffee.

My tips for brewing at higher altitudes (but I am by no means an expert!) are:

- Grind finer: A finer grind increases the surface area of the coffee, allowing for better extraction at lower temperatures.

- Pre-infusion: Bloom your grounds with a small amount of hot water before brewing. This helps saturate the coffee evenly.

- Extend brew time: Slightly longer brew times can help compensate for the lower temperature.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: