I’m sitting in my office, at home, watching the snow falling outside and it got me thinking….

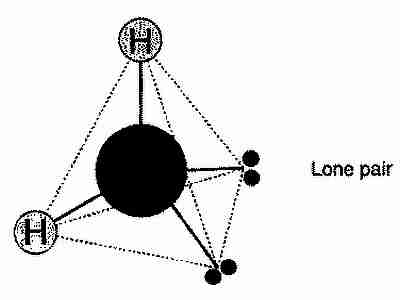

As is well known, chemically, water is made from hydrogen and oxygen (H2O), specifically, each water molecule is made from two hydrogen atoms bonded with an oxygen atom. In this bonding there are two left over pairs of electrons, and the whole molecule creates a rough tetrahedron.

“Luckily” (from the point of view of this post) when dealing with hexagonal ice (ice Ih) (i.e. natural ice /snow) we get a perfect tetrahedron (see here and here for more details of this), hence the six-fold symmetry in snowflakes.

Now we know this, we can work out just how unique the snow outside is, or the ice in your cup (perhaps you’re reading this in a warmer climate!) is. How many possible ways are there to create a tetrahedral structure like hexagonal ice?

With a little bit of thinking, and twisting the above image in your head, hopefully you’ll agree with me that there are 6 ways of arranging the water molecule in the ‘ice tetrahedron’. However, not every one of these possibilities is possible. Read the Wikipedia page on hydrogen bonds and then you’ll see that in fact only \(\frac{3}{2}\) possible orientations are allowed. That is, for a crystal of N molecules, there are \(\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^N\) ways to arrange the molecules inside that crystal.

So, let us consider a snowball, say of 3 cm radius. How many molecules are there in that much snow?

There are a number of ways of arriving at the number of molecules, but I’m going to go for the way which came to me first (rather than perhaps the best / most elegant solution (not that I know what that is!)). I considered the snow as water (because I know the molar mass of water!), so for that we just need to know the density of snow. Not so easy, it depends on various factors; as you have no doubt experienced, new snow feels a lot less dense then snow that has been sitting around for a week. Typically the densities vary between 8% and 50% the density of water. Once the snow is on the ground it settles under its own weight to a density of around 30%. Since the snow that got me thinking about this is fairly new, we’ll go for a density of 20%. That means 30 cm of snow would make 6 cm of water.

So our 3 cm radius snow ball has a volume of \(\approx 113\,cm^3\) which would be \(22.6\, cm^3\) of water. A cubic centimetre of water weights 1 grams so the water content of our snowball would weigh 22.6 g.

The molar mass of water is \(18.01528\, g\cdot mol^{-1}\) so there is \[22.6 \times\frac{1}{18.01528}\approx 1.25 \mbox{ moles}.\]

Multiplying this number by Avogadro’s number (\(6.02\times 10^{23}\)) yields the number of molecules in the snowball: \[1.25 \times 6.02\times 10^{23} \approx 7.5\times 10^{23}.\]

That means the possible number of orientations of the water molecules is \[\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{7.5\times 10^{23}} \approx 10^{10^{23}}.\]

So how big is that number? Well it is stupidly big. We estimate that there is something like \(10^{80}\) atoms in the universe which isn’t even close to that number. So it is safe to say that every snowball that has ever been made, or ever will be made by people all over the Earth for the rest of the history of this planet, will always have a unique arrangements of water molecules!

Or, if that was all pretty dull and you just want some pictures of snow, check out the BBC article about the current weather!